Introduction

In the course of my research for my historical fiction book Alina: A Song for the Telling, I happened upon the poetry of Yehuda Halevi, a poet from the 11th century, and felt as if I had come upon a pot of gold.

Halevi was a Renaissance man of his time—a renowned philosopher and poet, he also had a successful career as a physician. A compelling biography of Halevi by Hillel Malkin portrays Halevi as a poet, dreamer, and lover who straddled the secular and the non-secular world, managing to be both a profoundly devout man and one who loved the world in all its aspects.

Biographical facts

Jehuda Halevi was born in Spain around 1075, although there is some uncertainty about that date. There also is some uncertainty as to whether he was born in Toledo or Tudela. He appears to have spent some time in Granada, a hub of Jewish intellectual life at that time, where he studied with the Spanish philosopher and poet Moses Ibn Ezra. Halevi acquired comprehensive knowledge of traditional Jewish scholarship but also studied Arabic literature, as well as Greek sciences and philosophy, all while training as a physician. He wrote poetry and made a name for himself. Halevi eventually settled in Toledo, where he was already known for his work as a poet. Meanwhile, he continued practicing medicine.

Halevi had a daughter. She is referenced in his poems. We don’t know whether he had other children. According to some reports, this daughter was married to Isaac Ibn Ezra. Isaac’s father was Halevi’s good friend Abraham Ibn Ezra, a renowned Jewish biblical commentator and philosopher, born in Tudela in northern Spain, who also accompanied Halevi on some of his journeys to other cities in Spain and even to North Africa.

Concerned about the rise of fanaticism and intolerance in Spain, making Jewish life increasingly insecure, Halevi began to yearn for the land of Israel.

My heart is in the east, and I in the uttermost west.

How can I find savor in food? How shall it be sweet to me?

How shall I render my vows and my bonds, while yet

Zion lieth beneath the fetter of Edom, and I in Arab chains?

A light thing would it seem to me

to leave all the good things of Spain –

Seeing how precious in mine eyes

to behold the dust of the desolate sanctuary.

Halevi decided to travel to Israel in order to devote himself entirely to a religious life. He was already in his fifties or sixties, when he embarked for Alexandria from where he planned to go on to Jerusalem. In 1140, he arrived in Cairo, welcomed by friends who in the Jewish community. He stayed there for almost a year. However, sadly it does not appear certain that Halevi ever reached the Holy Land. A letter from a friend of Halevi’s reported his death in July 1141.

Philosophy

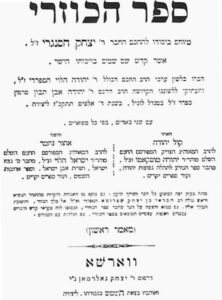

Halevi’s most well-known work is a philosophical treatise called the Kuzari. It consists of five parts and is written in the form of a dialogue between a rabbi and a nonbeliever. It explores complex questions of faith. Halevi wrote it in Arabic, and it was later translated into Hebrew.

[Book cover of a Hebrew language translation of the Kuzari by Judah Halevi. Warsaw, Poland, 1880.]

I cannot presume to comment on the intricate and fascinating aspects of Halevi’s thoughts laid out in the Kuzari. In this blog post, I merely want to highlight some of his poetry.

Poetry

While Halevi used Arabic in the Kuzari, he wrote his poetry in Hebrew even though he employed patterns of rhyming and strophes from Arabic poetry. His range was astounding. He wrote many religious poems, but he also touched upon themes ranging from friendship, grief, and loss to the pleasures of life and even riddles.

In light of the dearth of knowledge we have about Halevi’s life, both translators of Halevi’s poetry as well as his biographers are confronted with an essentially insurmountable challenge of refraining from attributing emotions and thoughts to Halevi and to convey these in translations of his writing.

Halevi’s writing is rich in allegories and allusions of a religious nature, and the themes of love, longing, and grief among others are touched upon through the defining lens of his faith. In other words, today’s reader may see the profoundly rich and even sensuous language while not perceiving the multiple layers of meanings contained in Halevi’s lines.

Here is an example where the reference is clear. Halevi speaks of his longing and his love for Jerusalem.

Earth’s delight and sovereign city

Longing from the ends of the west

For your lovely slopes, a tenderness

Stirs with me as I call to mind

Your past glory, your dwelling place

Now in ruin. I’d soar on eagle wings

If only to mix my tears with your dust.

But in other poems that capture my attention for the sheer beauty of the language, I would need a guide and translator to explicate the wealth of secular allusions in his phrasing.

Many of Halevi’s poems—in a sense you might say all of them—deal with the theme of love—love of country, love of friends, love of God, love of the Holy Land, love of life, and love of women.

The night when the fair maiden revealed the likeness of her form to me,

The warmth of her cheeks, the veil of her hair,

Golden like a topaz, covering

A brow of smoothest crystal—

She was like the sun making red in her rising

The clouds of dawn with the flame of her light.

Expressing the agony of the loss of a beloved person, Yehuda wrote these lines:

‘Tis a fearful thing to love what death can touch. A fearful thing to love, to hope, to dream, to be – to be, And oh, to lose. A thing for fools, this, And a holy thing, a holy thing to love. For your life has lived in me, your laugh once lifted me, your word was gift to me. To remember this brings painful joy. ‘Tis a human thing, love, a holy thing, to love what death has touched.

But what makes his poems so appealing—aside from the compelling imagery and music of the language—is the groundedness and an appreciation for the here and now.

When you’re with her, don’t go looking

for the sun, just as when she’s in your arms

she needn’t look for the moon.

That same sense of groundedness is reflected in the humor that lights up some of his short pieces.

Looking into the mirror I spotted

A single strand of gray air

And plucked out. “I’m easy game alone,”

It said, “but what do you plan

To do with my troops close behind me?”

In his last year of life, he wrote about his impressions of Cairo.

Has time taken off its clothes of trembling

And decked itself out in riches,

And has the earth put on fin-spun linen

And sets its beds in gold brocade?

How can one resist these lines, sensuous, reflective, and with self-irony, from what was arguably one of Halevi’s last poems?

Wondrous is this land to see,

With perfume its meadows laden,

But more fair than all to me

Is yon slender, gentle maiden.

Ah, Time’s swift flight I fain would stay,

Forgetting that my locks are gray.

Throughout his life, Yehuda Halevi corresponded with his friends and wrote many odes and elegies in their honor. His far-flung network of friends gives the impression of a supremely vibrant intellectual community that was not confined to any one locality. The following lines are part of a poem, the Ayin Nedivah (“Generous Eye”): Qasida for Solomon Ibn Ghiyyat, he had sent to his friend Solomon ibn Ghiyyat, with whom he traded writings and poems on a regular basis.

I can’t stop crying.

My eyes are like peddler women.

What they buy is: you are gone.

What they sell is: tears,

And business is good:

Enough tears for a jeweled necklace.

And an ode that begins with themes of mourning and loss, the Ayin Nedivah (“Generous Eye”): Qasida for Solomon Ibn Ghiyyat, ends with these life affirming lines:

A song, a poem for the reader to taste.

My tongue shall sing it on a glass of wine.

Conclusion

In conclusion, here is an excerpt from a poem called “On the Sea.” Halevi describes the perilous journey to the east and the dangers of the sea. It is a fascinating illustration of the strength of his writing, lyrical, compelling, grounded, and tangible, yet at the same time strongly evocative of his faith that sustains him again and again throughout the darkest days.

Has the flood come again and made the world a waste

So that one cannot see the face of the dry land,

And no man is there and no beast and no bird?

Have they all come to an end and lain down in sorrow?

To see even a mountain or a marsh would be a rest for me,

And the desert itself would be sweet.

But I look on every side and there is nothing

But water and sky and ark,

And Leviathan causing the abyss to boil,

So that one considers the deep to be hoary,

And the heart of the sea conceals the ship

As though she were a stolen thing in the sea’s hand.

Sources:

Halkin, Hillel. Yehuda Halevi. Schocken, 2010. [excellent biography of Yehuda Halevi]

Yehuda Halevi, Poems from the Diwan, translated from Hebrew by Gabriel Levin, Anvil Press Poetry: London, 2002

Selected Poems of Yehuda Halevi, translated by Nina Salaman, ed. By Heinrich Brody, The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1924.

Ayin Nedivah (“Generous Eye”): Qasida for Solomon Ibn Ghiyyat, translated by Joseph M. Davis, Gratz College (jdavis@gratz.edu) Copyright © 2006 Joseph Davis.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/halevi/ [excellent resource on Yehuda Halevi’s work Kuzari, including additional readings]

Images:

Book cover of a Hebrew language translation of the Kuzari by Judah Halevi. Warsaw, Poland, 1880.