Writing the biography of a parent, arguably one of the most important individuals in a person’s life, is challenging.

There are no six degrees of separation that allow a modicum of detachment. Complicated issues of privacy arise at every turning, and it is hard to reconcile the reflexive wish to protect the subject of the biography while offering an honest and meaningful portrayal.

How does one deal with the processes of distortion, inevitable in remembering interpersonal relationships? How does one deal with the gray zones and unknown areas in the life of a parent? How does one sort out the profound impact an individual has had on you from the portrait you are attempting to draw of that person? In my biography of my mother, I had to grapple with all these questions. An additional factor complicating this work is the concept of transgenerational trauma, a concept regrettably all too familiar to many people, e.g., the inherited shadows of the past, or to put it another way, the traumas experienced by one generation that have worked their way into the psyche of the second generation.

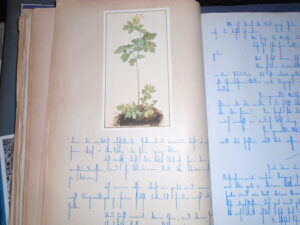

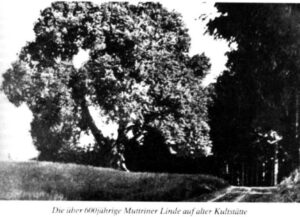

First and foremost a biographical account of a woman coming of age in Germany in the 1930s, Tapestry of My Mother’s Life was inspired by letters as well as stories told to her children. CHRISTA VON HASSELL’s story spans the 1920s to 2009; born in Farther Pomerania, a historic region along the Baltic Sea, in 1923, she attended university and married during World War II. Her father and her only brother died at the front in 1943, and her first husband died in a prisoner-of-war camp in the Soviet Union. Her maternal relatives, along with millions of other Germans, evacuated from Pomerania at the end of World War II, and Christa’s childhood home was to become a part of Poland. At the end of the war, she lived for three years under Soviet occupation. Christa von Hassell had to rebuild her life after 1945, faced with the loss of everything she had valued. This included not only her personal losses and the loss of her childhood home, but also the erosion of an entire social-cultural world and its moral-ethical value system. Her life experiences impacted her relationships in the post-war years, in particular, her interactions with her children.

The retelling of Christa’s life focuses on the role of memory and its impact on subsequent generations. I wanted to shed light on the process whereby children learn about their parents’ lives during extraordinary times and the ways in which a second generation seeks to come to terms with the inherited shadows of the past.

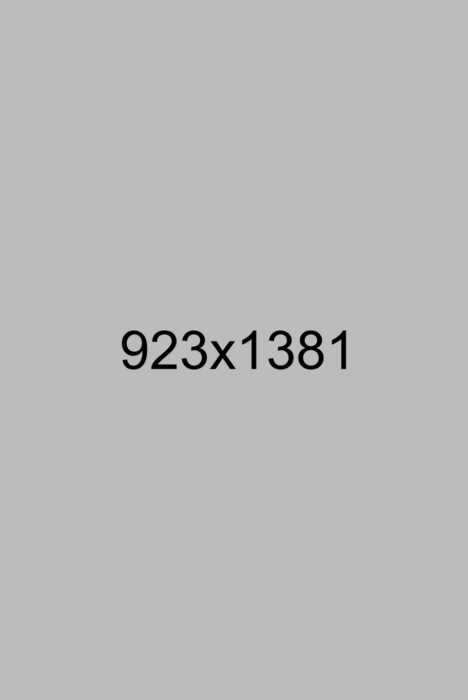

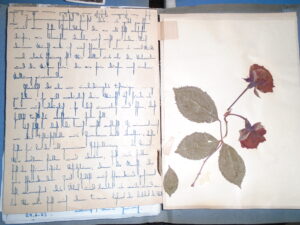

When writing this account, I drew on my mother’s stories, the papers she left behind, and my recollections of her throughout my childhood and as an adult. The final product is both a deeply personal account and at the same time a retelling of a story that has universal significance.

Throughout the process, I had to confront the huge gaps in my knowledge and the fact that my mother, like so many of her generation, kept silent about many aspects. This included, among others, the surreal experience of finding boxes of letters to my mother from a complete stranger.

My initial reaction when confronted with these letters was outrage. I was furious that my mother had left them for us to find. As it was, we had a lot to deal with when settling her affairs, but to come upon all these writings was too much. In retrospect, I found that the letters helped me to understand my mother better; I was able to gain insights into her vulnerabilities when she was still a very young woman and was experiencing an onslaught of emotions and losses difficult to absorb. It made me more understanding of some of these same vulnerabilities in the mature individual I knew in my years of growing up, for all that they were largely hidden from view.

Conveying the complexity of my mother’s life involved a continual reexamination of layers of privacy. There was the challenge of protecting her privacy and that of her correspondents; while drawing on those letters and her journal, I was keenly aware that these were private communications, never intended for publication. I had to walk a fine line between providing a forthright account while also refraining from invading her privacy.

The other layer of privacy emerged out of my mother’s experiences. Her sense of privacy, her reticence, and her silence on many subjects was the result of her upbringing as much as her experiences as a young woman.

Years of Nazi rule had a profound impact on the German language and lent this facility for doublespeak or ambiguity an additional layer of complexity. Victor Klemperer, a renowned scholar and writer, described how the Nazi era had perverted the impact of formerly innocuous words like mother, father, loyalty, truth, honor, faith, home, country, and countless others to the point that those who had lived through those years would always stumble over them, unable to shake the unwanted association like a bitter taste on the tongue or a stench one can’t forget. For people of my parents’ generation as well as the next one, the very act of speaking was filled with emotional minefields. My father recommended Klemperer’s book to me. “There is nothing the Nazis haven’t managed to stain,” he said with an expression of helpless despondency.

My mother reacted reflexively when confronted with particular terms. The word “Mother’s Day” is a case in point. When I was about three years old, a nanny helped me to collect wildflowers and told me I should present the bouquet to my mother for Mother’s Day. I don’t remember what my mother said at the time. Her rejection must have been more than explicit. I never dared to do that again; however, it wasn’t until much later that I began to understand why. The Nazis certainly didn’t invent Mother’s Day. In one form or another, it had already existed as a venerable tradition in many countries. However, during the 1930s, this day became indelibly linked with notions of women bearing children for their Führer. It was declared a national holiday, and women were awarded medals for their children. To this day, the very word makes me uncomfortable.

My relationship with my mother was subject to complicated and interrelated layers of silence. One was due to my mother’s personal makeup and strong sense of privacy. Furthermore, people of my parents’ generation and cultural background were raised to limit expressions of personal feelings or emotions. Another layer of silence emerged as the result of years of living under the Nazi regime, where often an ability to refrain from commenting might save your life as well as that of your relatives. This same protective and defensive silence becomes entangled with the silence out of fear, e.g., an ingrained habit of not speaking out about something that is wrong. The layers of silence on the part of my parents and other members of their generation also reflect an inability to deal with trauma in any other way and an overwhelming and unspeakable sense of horror at what their own country and fellow countrymen and women have perpetrated.

These silences were not unique to my mother. When one reads other accounts of women who have lived through those years, one encounters this same reticence. However, one can’t generalize and various forms of silence emerge out of different cultural and historical circumstances as well as unique traumas.

When I worked on my dissertation about Japanese women immigrants to America, I encountered similar barriers between the generations. Japanese immigrant parents tried to come to terms with the discrimination and racial hatred they experienced here and were intent on trying to protect their children. They thought that by staying silent about their own history to the extent of not even teaching their children Japanese, they would make it easier for their children to become fully integrated into American society.

Edmund de Waal, the author of The Hare With Amber Eyes, offers a multi-generational account of the history of a prominent Jewish family, originally from Odessa, Ukraine, affected by the Holocaust. Thus, the topic is different, and he focuses on an entire family rather than presenting a biography of one person. But just as I have attempted, de Waal explores the role of memory and silence between generations and the difficulty in telling the story since it involves digging in the private lives of those who have gone before us. He tries to piece together a complete story in the face of a vacuum of silence by surviving members and the fact that there are hardly any remaining physical traces of their former lives.

The shadows of the past continue to haunt subsequent generations. For my brothers and me, the stories of loss of home and deprivation, the violent deaths of my two grandfathers and others, and the experiences in the war as well as its aftermath left a profound impact on us. When I was a child and young adult, I often felt insignificant and even resentful about the large emotional space that they occupied, leaving little room for anything else.

The process of coming to terms with the lives of those who have gone before us whether as a parent or other relative is a universal challenge. The challenge is even greater when extraordinary circumstances such as a war or other traumas are involved and impact the relationships with the second generation. However, this is not an insurmountable challenge. We can learn from those who have gone before us, but we are not defined by them, free to work on our lives as we see fit and to create our own footprints.