In a deleted chapter in my historical fiction book, The Falconer’s Apprentice, my protagonist Andreas, after a long journey, is on his way to Salerno, carrying a letter of recommendation from Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen in his pocket. Arriving at the courtyard of Maahir Ibn Ghaiyyas, Andreas comes upon a chaotic scene, a woman in the last stages of labor and a man screaming at a bewildered servant who disappears in the house in search of towels and boiling water. The man shouts at Andreas to come and help. After the successful delivery, he turns to Andreas.

— Start of excerpt:

“Who are you?” The slender little man peered at Andreas over the rim of his leather bag, his silvery beard quivering in the breeze. “What do you want?”

Andreas pulled out the envelope and held it out.

Maahir Ibn Ghaiyyas squinted at the seal. “A letter from Emperor Frederick? Come in.”

Andreas followed him into his study.

“Sit.” In a burst of irritation, the doctor tossed his bag into a corner and swept some manuscripts from the chair in front of his desk. “It’s not a good day. My assistant left unexpectedly, and my servant faints at the sight of blood. I am expected at the university in an hour. Let me take a look at this letter.”

He opened a drawer and pulled out an odd shaped wire structure with two oval glass pieces and placed the contraption on his nose. It made him look like a cynical bearded owl. He opened the letter and read it without changing his expression. Then he pushed the wire frame down on his nose with his slender long fingers and peered at Andreas over the rims as if Andreas was a specimen about to be analyzed.

Andreas stifled an impulse to giggle. “Sir, what’s that?” He pointed at the wire frame.

“This?” The doctor pulled the frame off his nose and held it up. “It’s a new invention. These are called spectacles. I am delighted with them. Here, try them.”

Andreas placed the frame on his nose and looked around. He blinked; everything was blurry.

“How is this supposed to work? I can’t see well with it at all.” He took off the contraption and gave it back.

“Ah, that is because spectacles are meant for older people whose eyes are getting weaker. I can’t tell you how they work; there is someone at the university who is studying eyes. She might tell you more if you are interested. Anyway, let’s see what to do about you. This letter,” he put his hand on the envelope with the imperial seal, “vouches for you, though it does not state what it is you can do.”

Andreas hesitated. He doubted that his peripatetic activities over the past year would be much of a recommendation. Carefully, he said: “You said your assistant left. Is he coming back?”

The doctor said with a shudder. “Oh, I hope not. He insisted on bleeding my patients whenever he got a chance. This morning, when that hapless man brought in his wife in the midst of her labor, my assistant wanted to bleed her. I put a stop to that and told him to leave. A little knowledge is a dangerous thing in the hands of an imbecile! I am glad he is gone, but it is terribly inconvenient—it will be months before new students come to the university. I really don’t have time for hunting around for a new assistant.” Distractedly the doctor pulled on his beard, and he frowned. Then his eyes brightened. “You look like a sensible young man, and you can follow instructions—that’s more than one can say for most people. What about it? Do you want the position?”

“Yes, I want it very much.”

“Well, then that’s settled. You will get room and board and an allowance. But right now I need to go the university. You can come along. Stable your horse and wait for me in the courtyard.” — end of excerpt

For my protagonist, who dreamed of becoming a healer, arriving in Salerno must have been a heady experience.

The Scuola Medica Salernitana traces its origins back to the 9th century. In the Middle Ages, it was one of the foremost medical schools and disseminators of medical knowledge in Europe.

Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, was a strong supporter of the school. According to the Constitution of Melfi, established in 1231 for the governance of the Kingdom of Sicily which included southern Italy as well as the island of Sicily, a doctor could only practice medicine if in possession of a diploma issued by the Scuola Medica Salernitana.

There is a touching legend about an event that supposedly led to the foundation of the school. According to this legend, the foundation of the school can be traced back to a happenchance encounter of four individuals. It is reported that a Greek pilgrim named Pontus had stopped in the city of Salerno and found shelter for the night under the arches of the Arcino aqueduct. There was a thunderstorm and another Italian runner, named Salernus, wandered in the same place. He was hurt and the Greek, at first suspicious, approached to look closely at the dressings that the Latin practiced to his wound. Meanwhile, two other travelers, the Jew Helinus and the Arab Abdela had joined them. They also showed interest in the wound, and at the end it was discovered that all four were dealing with medicine. They then decided to create a partnership and to give birth to a school where their knowledge could be collected and disseminated.

Regardless of the truth of this story and the fascinating image of a Latin, a Greek, a Jew, and an Arab joining forces to create a school of medicine, undoubtedly the Scuola Medica Salernitana was a remarkable institute of learning. Truly a crossroad of cultures, medical practitioners were open to medical knowledge and practices from the East and the West, drawing on texts translated from Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic and willing to blend medical practices that had their roots in the teachings of Hippocrates and Galen with Arab medical practice. As an example of the remarkable flow of information between East and West, one might consider Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine, written in 1030, which drew on medical knowledge from Greek, Indian, and Muslim physicians. It is noteworthy that the emphasis of the school was on developing best practices for prevention rather for finding cures.

Furthermore, medical practitioners, teachers, and students at the Scuola Medica Salernitana included both men and women.

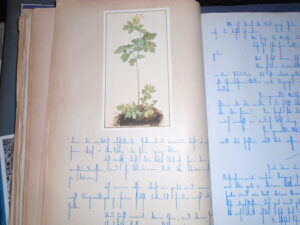

Care of patients

Care of patients

Some of the women whose names have become part of the historical record were known as the “women of Salerno.” Among these was Rebecca Guarna, a physician, surgeon, and author from the 13th century; her books dealt with the study of urine and fever, among others. Another was Abella, presumably born in 1380, who lectured at the university and also authored works on the study of bile as well as the study of seminal fluid. Mercuriade was a physician and surgeon in the 14th century; she produced works entitled “On Crisis in Pestilent Fever” and “on the Cure of Wounds,” among others. Calenda was a 15th century physician and surgeon who specialized on diseases of the eye.

Perhaps the most well-known of the mulieres Salernitanae or “women of Salerno” is Trota de Ruggiero, who lived and worked in Salerno in the 12th century.

Pen and wash drawing showing a female healer, perhaps Trota of Salerno, clothed in red and green with a white headdress, holding a urine flask to which she points with her right hand.

While Trota was almost certainly not the sole author of a compendium of texts on women’s medicine that acquired the name Trotula or ‘little book,’ she was unquestionably an influential medical practitioner with a broad range of interests. Known, among others, for her compendium of cures known as “Practical Medicine According to Trota,” she wrote texts on gynecology, obstetrics, and women’s health, infertility, internal diseases, fevers, and wounds, as well as intestinal and ophthalmic disorders. Her writings were widely read in the subsequent centuries. Trota was even interested in male infertility, remarkable given prevailing notions at the time that a failure to conceive was generally assumed to be the woman’s “fault.”

Pages of text attributed in part to Trota of Ruggiero, De ornatu mulierum.

Pages of text attributed in part to Trota of Ruggiero, De ornatu mulierum.

In any event, the work done by Trota and her female colleagues at the Scuola Medica Salernitana in a setting that embraced medical practices from different cultures offers a refreshing new perspective on an era at times characterized as the so-called ‘Dark Ages.’

I like to envision my protagonist from The Falconer’s Apprentice absorbed in his studies at the Scuola Medica Salernitana, studying Greek and Arabic and even Hebrew so as to be able to pour over medical texts in their original languages, and perhaps even journeying to the east to learn at the hand of masters of the art in Cairo or in the Byzantine empire.

Sources

Alic, Margaret, Hypatia’s Heritage: A History of Women in Science from Antiquity to the Late Nineteenth Century, The Women’s Press, 1986.

Barratt, Alexandra, editor, The Knowing of Woman’s Kind in Childing: A Middle English Version of Material Derived from the Trotula and Other Sources, Medieval Women: Texts and Contexts 4, Brepols Publishers n.v., 2001.

Green, Monica Helen, The Trotula: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

Riesman, David, The Story of Medicine in the Middle Ages, Paul B. Hoeber, Inc., 1935.

Online resources:

Exhuming Trotula, Sapiens Matrona of Salerno, Florilegium (January 19, 2004) https://www.medievalists.net/2011/01/exhuming-trotula-sapiens-matrona-of-salerno-2

Social Aspects: Women, Medieval Medicine, http://www.intermaggie.com/med/women.php

(January 19, 2004).

Trotula of Salerno, Malaspina Great Books, (January 19, 2004),

http://www.malaspina.com/site/person_1140.asp

Women Scientists of the Middle Ages & 1600s, Academic Forum Online,

http://www.hsu.edu/faculty/afo/2000-01/merritt1.htm (January 19, 2004).

Images

1. Care of patients

http://www.stupormundi.it/it/sites/default/files/archivio/scuola-medica-salernitana.jpg

2. Trota of Salerno with text as background

London, Wellcome Library, MS 544 (Miscellanea medica XVIII), early 14th century (France), a

copy of the intermediate Trotula ensemble, p. 65 (detail): pen and wash drawing meant to depict

“Trotula”, clothed in red and green with a white headdress, holding an orb

By Miscellanea medica XVIII – Wellcome Library, London, CC0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31154428

3. Book: Trotula transitional ensemble, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat.

7056, mid-13th century, ff. 84v-85r, opening of the De ornatu mulierum.

By PHGCOM – Own work by uploader, photographed at Musée de Cluny, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6832867