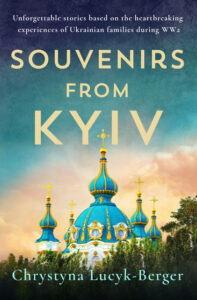

While researching for my historical fiction book, The Falconer’s Apprentice, I came across a work entitled The Art of Falconry, also known as De Arte Venandi Cum Avibus. The author of this treatise on ornithology and falconry, written in Latin the 1240s, was Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

The history of falconry is inextricably linked with that of Frederick II as well as with his favorite son Enzio, known as Falconello or ‘the Little Falcon.’ Frederick II was an avid hunter and maintained extensive mews for his birds of prey. When on the road, his menagerie often traveled with him. In fact, some historians have argued that the emperor lost a decisive battle against the city of Parma in 1248 because at a critical moment he had gone off to hunt rather than staying with his army. According to a legend, a white gyrfalcon appeared at every major turning point in the emperor’s life, and his soul was said to have turned into a falcon upon his death.

Frederick II (26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was known as ‘stupor mundi’ or the ‘wonder of the world’ for good reason. Born in Sicily in 1194, he spoke at least 6 languages including Arabic. He was avidly curious about the world, supported math and sciences, and commissioned translations of scientific works from Hebrew, Greek, and Arabic. In 1224, Frederick II founded the University of Naples Federico II, the world’s oldest public non-sectarian institution of higher education and research. The emperor supported the medical university of Salerno, the Scuola Medica Salernitana, remarkable for the fact that professors and students included both men and women. Frederick II was a poet in his own right and founded the Sicilian School of Poetry. He also was actively involved in the design and construction of many notable structures throughout southern Italy. One of the most famous of these is Castel del Monte in Apulia. [See https://www.malvevonhassell.com/castel-del-monte/]

Frederick II, who included King of Sicily, King of Germany, King of Italy, and King of Jerusalem, as well as Holy Roman Emperor in his titles, spent over thirty years working on De Arte Venandi cum Avibus. In his prologue, he apologizes that it took him a long time to finish this work but that he had some other things to do as well, referencing “arduous and intricate governmental duties” that occupied much of his time.

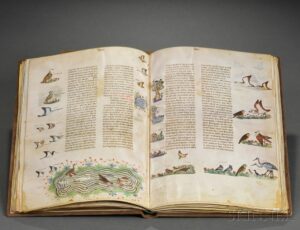

The Art of Falconry is an astounding compendium that draws on a variety of sources such as literature from the Middle East and the emperor’s own observations and experiments. For instance, he experimented with eggs to see if they would hatch only by the warmth of the sun, and he tried to find out if birds used their sense of smell while hunting by covering the eyes of vultures. The work addresses everything from the proper habitat for birds of prey, their capture, breeding, and training, their feeding and medical care, and even a chapter on how to release a falcon back into the wild.

The entire work, highly organized and arranged like an academic tome, consists of six books that addresses the following subjects at great length and in exhaustive detail.

Book I: The general habits and structure of birds

Book II: Birds of prey, their capture and training

Book III: The different kinds of lures and their use

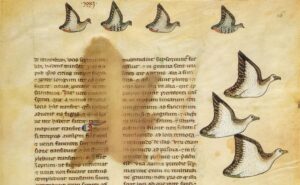

Book IV: Hunting cranes with the gerfalcon

Book V: Hunting herons with the saker falcon

Book VI: Hunting water-birds with smaller falcons

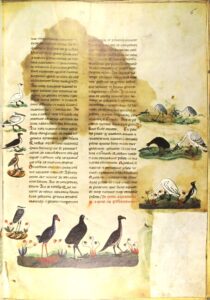

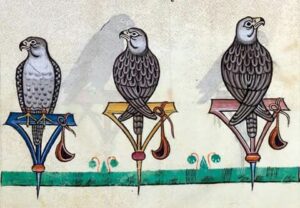

Of the seven extant copies containing two books, the most famous one is a beautifully illuminated manuscript commissioned by the emperor’s son Manfred; it is housed in the Vatican Library. There are six copies with all six books. One, dating from the 13th century, is housed in the Biblioteca Universitaria in Bologna.

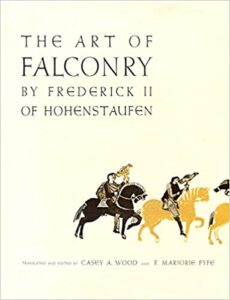

The edition prepared by Casey Albert Wood and Florence Marjorie Fyfe includes not only an excellent translation but also various scholarly articles that provide helpful context for this astonishing compendium. Meanwhile, if you are interested in seeing the many colorful illustrations, you would be better advised to look elsewhere. The printed version of all six books spans 415 pages.

Falconry was central to medieval life and culture. It had practical value in providing meat; some form of hunting with birds of prey was permitted at all levels of society. As an activity practiced by the upper classes, it also was a luxury and a status symbol.

The training of falcons involves a great deal of experience and patience on part of falconers. A falconer was responsible for capturing, training, and caring for the birds. The main goal in training these wild creatures was to teach them to accept captivity and to return to it. A falconer also was responsible for making the gear used to work with falcons such as the leather hoods, jesses or leg straps, bells, lures, and leather gloves for the owners. In the Middle Ages, the position of falconer was generally handed down from father to son. An official position at medieval courts was Royal Falconer. This person ranked fourth after the king himself.

In medieval times, falcons were protected. That is, anyone who disturbed a nest was punished. In Austria in the 15th century peasants could be blinded or have their property confiscated. The punishment for destruction of a falcon’s egg could be one year’s imprisonment; an individual who poached a falcon from the wild risked having his eyes poked out as a punishment.

In the Middle Ages, the rules of falconry reflected the social order. Birds of prey, including the large and smaller falcons as well as hawks, were ranked in a strict hierarchy, specifying who could own what type of bird. These ranks mirrored and reinforced the social ranks in Europe in those days, with women, priests, servants, and children at the bottom of this hierarchy.

King Gyr Falcon

Prince Peregrine Falcon

Duke Rock Falcon (subspecies of Peregrine)

Earl Tiercel Peregrine

Baron Bastarde Hawk

Knight Saker

Squire Lanner

Lady Female Merlin

Yeoman Goshawk or Hobby

Priest Female Sparrowhawk

Holy water clerk Male Sparrowhawk

Knaves, servants, children Kestrel

Acceptance of the social order in a clearly structured social universe was viewed as the main bulwark against chaos, while freedom was possible only within the parameters of this order. The hierarchy of humans and birds was strictly observed. Keeping a bird of prey above one’s station was punishable; it could even mean having one’s hands cut off. Falcons were treated with honor according to their rank in the hierarchy of birds. This meant ironically that they also could be punished as if they were persons of rank. Emperor Frederick had a falcon beheaded for transgressing against the social order by killing its lord. That unlucky falcon, sent after a crane, had veered off and brought down an eagle, the lord of birds. In another story, the King of Persia’s falcon also was punished after killing an eagle. Yet, the culprit was accorded the respect due to a royal bird. It was first placed upon a dais and crowned in recognition of its bravery before being beheaded.

The treatise about falconry by Frederick II is both a comprehensive record of knowledge about falcons and hunting with birds of prey in the 13th century and a set of life lessons applicable to falconers as much as anyone wanting to succeed in life. The world of hunting with birds of prey served as a mirror to the accepted social order while also providing a literal training ground for individuals living in that society.

The Falconer’s Apprentice is set in the intense social and political unrest of the Holy Roman Empire in the thirteenth century. The protagonist Andreas, a 15-year-old orphan and apprentice falconer, embarks on a precipitous flight across Europe to rescue the falcon Adela. Andreas, assistant to the head falconer in a castle in the north of Germany, is appalled when his young lord imposes the death sentence upon a young peregrine falcon. In deciding to hide and ultimately escape with the falcon, Andreas breaks several laws of medieval society—failing to obey a direct edict from his lord and stealing, both subject to severe punishment.

I drew on excerpts from The Art of Falconry to illustrate elements of the life lessons my protagonist learns and the challenges he encounters on his journey from northern Europe to southern Italy.

For instance, the discussion of what makes a good falconer, e.g., patience, hard work, and willingness to study, could apply to anyone trying to be successful.

“The falconer must not be one who belittles his art and dislikes the labor involved in his calling. He must be diligent and persevering, so much so that as old age approaches he will still pursue the sport out of pure love of it. For, as the cultivation of an art is long and new methods are constantly introduced, a man should never desist in his efforts but persist in its practice while he lives so that he may bring the art itself nearer to perfection. He must possess marked sagacity; for though he may, through the teachings of experts, become familiar with all the requirements involved in the whole art of falconry, he will still have to use all his natural ingenuity in devising means of meeting emergencies.”

Bad training and lack of attention have a detrimental impact on the animals in your keeping.

“Falcons and other hawks are rendered clumsy or entirely unmanageable if placed under control of an ignorant interloper. By using his hearing and eyesight alone, an ignoramus may learn something about other kinds of hunting in a short time; but without an experienced teacher and frequent exercise of the art properly directed no one, noble or ignoble, can hope to gain in a short time an expert or even an ordinary knowledge of falconry.”

Controlling one’s temper is of paramount importance.

“A bad temper is a grave failing. A falcon may frequently commit acts that provoke the anger of her keeper, and unless he has his anger strictly under control, he may indulge in improper acts toward a sensitive bird so that she will very soon be ruined.”

Frederick II offers instructions on how to travel with a falcon.

“Before starting out on a long journey the bird should, for a few days, be made familiar with her hood until she either ceases her restless activities altogether or at least abandons the worst of them. She should also be handled and carried about more than if she had no journey to make.”

In one of the segments, the author addresses the proper care of a bird in captivity. I found this particularly moving in light of the fact that the emperor’s favorite son, King Enzio of Sardinia, was captured by his enemies at the Battle of Fossalta in 1249. Despite repeated attempts by the emperor and others, Enzio remained imprisoned in Bologna until his death in 1272.

“When a suitable location for the care of falcons has been found, an artificial nest must be built of materials like those of the wild eyrie. This place should be open on three sides (to the north, east, and west breezes) and exposed to the morning and evening sunshine.”

An entire section is dedicated to how to return a falcon to the wild. My protagonist decides to release his beloved falcon Adela in the hills of Apulia.

Andreas spoke to Adela as he had always done, in an easy relaxed voice. “No more traveling in a little cart for you. Today you will fly as high as you want. Maybe you will meet some brothers and sisters. You will finally get to do what you do best. You’ll see. You’ll be fierce and powerful and free.” Andreas thought of running his hand over her back and wings, but stopped at the last instant.

“A falcon is not a lap dog. It is a wild animal. Never forget that!” Oswald had told him over and over again.

It was time. Andreas secured the leather glove on his arm and put out his arm. She stepped onto it willingly. He slipped the hood over her head and began to walk up the narrow deer trail, careful to keep his arm steady so that she would be relaxed and calm.

He quickly reached the top. The tree growth had thinned out, and he could look into the plain below and the range of hills along its edge. Andreas waited, watching the sky and the trees around him. For a moment, he thought about flying Adela and recalling her one more time. No, Adela was going to need all her energies in the next few hours. He pulled off the long jesses on her ankles so that they would not became a source of danger to her in the wild and removed the little bell attached to her left foot just above the jess.

A large bird flew across the sky in the distance. Andreas lost sight of it again. Perhaps it was a falcon. He did not know how territorial other hunting birds would be. In any event, there was not much he could do about it; it would be up to Adela. If all went well, Adela would eventually find a mate. Oswald had told Andreas that falcons mate for life.

A flock of small birds swept across the tree line. Andreas took the falcon’s hood off. He could sense her mounting excitement as she scanned her surroundings. He relished the firm grip of her talons on his arm. Once more, Andreas looked at the impenetrable shiny black eyes, the sharp black bars on her chest and back, and the luminous blue of her legs. Then he lifted his arm and gently launched her into the air.

Adela rose swiftly, climbing higher and higher, her wing beat steady and powerful. She swooped and circled, scanning the area for prey. Something must have caught her attention beyond the tree line, because she banked sharply. Andreas followed her with his eyes as she headed toward the range of hills in the south. Then she was gone.

Andreas gazed into the distance. His throat hurt. He wanted to cry, and yet he had never in his entire life been quite as exhilarated as when he watched Adela take off into the morning sky.

Sources:

Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, author, Casey A. Wood, translator, and F. Marjorie Fyfe, translator. The Art of Falconry, being the De Arte Venandi cum Avibus of Frederick II of Hohenstaufen. Stanford University Press, 1943.

Images:

- Drawing of Emperor Frederick II, by Serena Lisi, owned by Malve von Hassell

- Drawing of falcon in flight, by Serena Lisa, owned by Malve von Hassell

- Images from De Arte Venandi cum Avibus, Public Domain {{PD-US}}Bibliotheca Vaticana, Pal. Lat. 1071. folio 16r [birds in flight] File:De Arte Venandi com Avibus.jpg

Publico dominiovedi termini File:Falconry Book of Frederick II 1240s Deer and Birds.jpg

Detail of two falconers. Illustration from De arte venandi cum avibus. Ms. Pal. Lat. 1071, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana