On February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine in a full-blown, no-holds barred assault that resulted in devastated communities all over the country, unspeakable atrocities, and loss of life for both civilians and soldiers. The world has been transfixed by the resistance marshalled by Ukrainians in a veritable David versus Goliath confrontation and their unbending determination to defend their independence, their culture, and their young democracy.

The Ukrainian writer Olena Stiazhkina kept a diary with entries for every day of the war. Her words reflect the agonizing struggle between the wish to bear witness and the utter impossibility of wrapping one’s mind around what was happening. On Day 53 of the war, she wrote:

“April 17. What my eyes have seen. Now we have the chance to understand first-hand whether [German philosopher] Theodor Adorno was right when he said that, “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” I don’t know whether, after the event that we call “Bucha” but which in fact has dozens of other names, I will be able to write anything. Everything I’ve written up until now feels like flat words and singed letters with airless space between them.”

Meanwhile, we are not only stricken and overwhelmed by the horrendous details of this war that come to us via the media on a daily basis. We are also dazzled and bewitched by the stunning resilience and spirit displayed by Ukrainians.

Ukraine has fragile democracy in a country riddled with challenges and always under the shadow of Russia. Yet the weeks and months since the start of the war have shown the world a people who face the world with inventiveness, an enduring humanity, and even the gift of laughter.

One example is the manner in which the armed forces operate, with a decentralized modus operandi, each individual thinking and actively engaging in the decision-making process. This is also evident at many other levels. According to reports, occupying forces in occupied regions of Kharkiv Oblast have been puzzled and amazed by the self-organization of Ukrainians, stating that “in Russia, things would have been different. No one would have done any volunteer work.”

In another instance, the residents of Demydiv flooded their village intentionally, along with a vast expanse of fields and bogs around it, creating a quagmire that thwarted a Russian tank assault on Kyiv and bought the army precious time to prepare defenses.

We have seen countless images of farmers, cheerful and undaunted, putting their tractors to good use in the middle of a theater of war. Farmers, intent on preserving the lives of their dairy cows, hit on the expedient of tying them to stakes at great distances from each other, thus allowing them to graze and at the same time ensuring that only one or two would get hit during a missile strike. A baker in Kharkiv continues to bake despite shelling going on all around him. People make music inside bomb shelters. Ukrainians have creatively revamped their businesses in order to support the military. Rescue workers in the aftermath of a missile attack dig among the bricks until they extract a tiny dog. The owner, an old man who already lost everything, is in tears when the rescue workers hands him the dog. In the dystopian landscape of Mariupol, once an attractive city, a mother plants spring bulbs on a little plot in front of her building, while her young child watches.

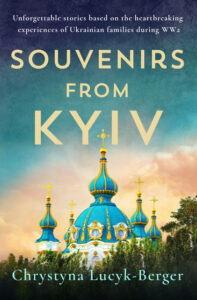

It is against this backdrop that Chrystyna Lucyk-Berger decided to reissue her book Souvenirs from Kyiv. I am thrilled that this collection of stories has been released in a new edition. It is one of the best books I have read in a long time.

In her introduction, Lucyk-Berger writes about the now famous salute Slava Ukraini, Glory to Ukraine. She argues that “to understand the power of this salute, you must understand its history.” And a complex history it is, reaching back to Ukraine’s War of Independence (1917-1921), the struggles of the partisans in the 1940s with their in some respects problematic aspirations, and its reemergence in 1991.

“The salute is mired in blood and in sacrifice even as its meaning has shifted to unify an entire world. And maybe that is okay if the words are not lost in a vacuum; if the words—which mean so much—can be understood.”

Souvenirs from Kyiv was inspired by accounts of the author’s family members who lived through the horrors of World War II in Ukraine, in the labor camps in Germany, and in displaced persons camps after the war. While the book is pitched as a collection of separate stories and each can indeed be read independently, the stories are loosely linked through family connections and a consecutive time frame. Together they form an arc of heartrending history.

The author does not offer a portrait in black and white; instead, she is willing to render the many overlapping shades and conflicting motivations that drove people in those years to act as they did. As one of her protagonists says “I know that one oppressor is no better than the next.”

Lucyk-Berger’s writing is stunning. With short, terse sentences, she wrings lyrical beauty out of experiences that shatter the soul. Exquisite details lend color and texture to the stories; for instance, at one point, in order to ease tensions and distract enemy soldiers, one character in the book engages the soldiers in a game of egg cracking—something we always played at Easter. Against the backdrop of one of the most heartbreaking and devastating set of decades in Ukrainian history, starting with the vice grip exerted by the Germans and the Soviets in turn, and the excruciating aftermath including the diaspora of Ukrainians after World War II, Lucyk-Berger conveys the remarkable resilience of Ukrainians, whose family spirit, generosity, and sense of humor shines through. The author provides a short glossary which is very helpful for those not so familiar with the history.

In her introduction, the author says: “Thanks to Hollywood, we are conditioned for that happy end to arrive within ninety minutes. In war, it does not. And the impact is felt over generations.” Ukrainians will struggle with the impact of what has happened since February 24, 2022 for a long time to come.

Sadly, history repeats itself, and some of the scenes playing out in front of our eyes today, might well belong in Chrystyna Lucyk-Berger’s stories. The echoes are bitter and painful. The stories offer important historical context for present events. But they also inspire hope in highlighting so much of what we have come to love about Ukraine.

About the book:

‘Russia has been trying to wipe Ukraine off the world map for thousands of years. They haven’t succeeded yet. Now, I’m picking up my stone and throwing it at Goliath. I want people to understand. I want to save this country.’ Chrystyna Lucyk-Berger, March 2022

Larissa is a renowned embroiderer, surviving in occupied Ukraine during World War II as a seamstress in her ruin of a workshop. Surrounded by enemies, she expresses her defiance by threading history into her garments. But at what cost?

Mykhailo is a soldier on leave, returning to Ukraine from the front on Christmas Eve. As he travels through his country, he is confronted by the hardship the war has brought to his fellow countrymen. Will what he sees this Christmas change the course of his life forever?

Marusia and her family are woken early one morning by the arrival of the Nazis, who have come to search for her partisan brother. As the soldiers move through their house, her family has just moments to make choices that will determine their survival.

Chrystyna Lucyk-Berger’s stories bring to life the true history of her Ukrainian family who fought to survive World War II. Laced with hope, Souvenirs from Kyiv celebrates the endurance and resilience of the human spirit.

Souvenirs from Kyiv was awarded 2nd Place in the 2014 HNS International Short Story Award and the collection won the silver medal in the IPPY Book Awards 2020 for Military and Wartime fiction.

You can purchase a copy of the book here.

To learn more about this book and other work by Chrystyna Lucyk-Berger, visit her website. You can also follow her on Twitter and on Facebook