“[Andreas] walked across the Piazza Maggiore and looked at the palace where Enzio was imprisoned. In the half light of the early evening, its clean lines and simple grey-pinkish sandstone façade gave the building a soft and inviting character. It was hard to think of this elegant edifice as containing prison cells and dungeons. The roof was lined with whimsical looking sickle-shaped merlons, the stone structures sticking out all along the parapet, reminding Andreas of neatly folded bishops’ hats sitting side by side. In one area of the building, an arcade opened onto a courtyard, giving the building an almost church-like aspect.” [Scene from my historical fiction novel The Falconer’s Apprentice, set in the 13th century]

This is where King Enzio of Sardinia spent the last 23 years of his life as a prisoner of Bologna from 1249 to 1272.

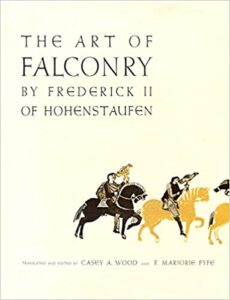

Enzio (from the German name Heinrich, sometimes rendered as Enzo) was an illegitimate son of Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen and by all accounts his favorite. They shared a love for falconry and poetry among others, and Frederick II valued his son as a capable leader and commander.

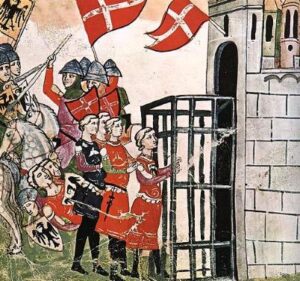

Enzio was 24 when he was captured at the Battle of Fossalta during a battle with the Guelphs, a powerful faction in northern Italy opposed to the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Frederick II repeatedly demanded the release of his son, but to no avail.

In the Middle Ages the city of Bologna was a powerful city state. By the end of the 12th century it had succeeded in establishing relative autonomy from imperial authority and began to turn itself into one of the main commercial trade centers of northern Italy. It also was home to the world’s oldest university in continuous operation to this day; in the Middle Ages, the University of Bologna was renowned for the study of law and medicine among others.

Located in the center of the city on the Piazza Maggiore, the Palatium Novum or New Palace was built as an extension of the municipal Palazzo del Podestà between1244 and 1246. Accordingly, it was outfitted with various spaces for representational purposes, offices for city officials, as well as additional prison space. On the right of the palace is the access to the chapel of Santa Maria dei Carcerati. Here those condemned to death could say their last prayers. The first floor housed the Carrocio, a large vehicle on wheels decorated with a standard which served as a rallying point for an army in battle. The war machines were also kept on the first floor, while offices were on the middle floor. Today the Palatium Novum is known as the Palazzo Re Enzo after the royal prisoner who lived there until his death.

There were repeated fruitless attempts to free Enzio. One of these involved the plan to hide him in a barrel of beer that would be rolled through the city streets. Meanwhile, even by modern standards, Enzio’s prison was relatively luxurious—unlike that of other knights captured during the same battle who spent painful days in dark dungeons until someone paid their ransom. The city, inordinately proud of her royal hostage, had set up an apartment in the palace where Enzio could spend his days reading, writing, and receiving visitors. Meanwhile, at night his guards placed him in a room with bars. This story gave rise to the legend that Enzio was kept in a cage hanging from the ceiling.

Until his death Enzio continued to hold the reigns as King of Sardinia. He was passionate falconer, and his father’s nickname for Enzio was Falconello or “Little Falcon.” I like to imagine that Frederick II shared excerpts of the voluminous compendium about the art of falconry which he was writing with his son by sending copies to Bologna. A translation from the Arabic into French of a hunting treatise was dedicated to Enzio. Enzio also was a respected patron of the arts, with a particular interest in music and poetry.

Enzio was allowed to receive female visitors, and he fathered three natural daughters while in Bologna. According to unconfirmed claims, Enzio also had an affair with a peasant woman by the name of Lucia di Viadagola. According to the legend, their son was called Bentivoglio, from the words Amore mio, ben ti voglio, supposedly the words Enzio spoke to his beloved (“My love, I’m fond of you”). This same Bentivoglio is said to be the ancestor of the Bentivoglio family, one of Bologna’s power players and even rulers of the city in the 15th century, albeit for a brief time only.

Despite these concessions and relative comfort of his captivity, for a young and active man it must have been hard to endure, cut off from the world of power and politics he had been born into, from the vibrant intellectual life at his father’s court, and from any hope of pursuing his favorite sport—flying falcons in the hills of southern Italy. By the time Enzio died in 1272, he had been forced to witness from afar the collapse of his father’s empire, the death of his father and surviving brothers, and finally the execution of Enzio’s nephew Conradin in 1268 at the hands of Charles of Anjou. Enzio continued to live behind bars while the Hohenstaufen dynasty came to a bitter end.

Yet in those years, Enzio wrote poetry. Together with his father Frederick II and his half-brother Manfred, Enzio was a founding member of the Sicilian School of Poetry, which was inspired by the lyrics written by troubadours. The Sicilian School of Poetry helped to establish the vernacular as the standard language for Italian love poetry and to invent two major Italian poetic forms, the canzone (a form of lyric poetry in the Italian style, of Provençal origin, that closely resembles the madrigal) and the sonnet.

Enzio is credited with several canzones, a sonnet, and fragments, although scholars disagree about the attribution of some of these. They are compelling and moving, in particular when one considers the circumstances under which they were written.

La Notte

No, non e’ dorme: s’è addormito il mondo

intorno a loro. Ei solo è desto, e vede

l’acque dormire, lieve ansare i venti,

chiudere il cielo gravi le sue stelle,

sparir la terra. Liberi e sereni

sentono il tutto che s’annulla preso

dalla dolcezza antelucana.

Eya! gridate, Eya! gridate a vuoto

l’ultima volta, o guaite del palagio!

Ed ecco suona la campana.

THE NIGHT [translated by Malve von Hassell]

No, not ‘asleep—all the world around him

sunken into torpor. He alone is awake; his gaze

Travels across the silken seas, gentled by the wind.

The heavy skies have imprisoned the stars,

And all land disappears.

Free and serene, emptied of longing,

He is lost in the sweetness of dawn.

Eya! Shouts fill the void. Eya!

Once more, the clamor of the palace!

And the bell tolls.

Heartbreaking and filled with raw grief is the poem entitled Amor me fa sovente.

Amor mi fa sovente

lo meo core pensare,

dàmi pene e sospiri;

e son forte temente,

per lungo adimorare,

ciò che poria aveniri.

Non c’agia dubitanza

de la dolze speranza

che ’nver di me fallanza ne facesse,

ma tenemi ’n dottanza

la lunga adimoranza

di ciò c’adivenire ne potesse.

[Translated by Malve von Hassell]

So often have you, my love, made it so that

sorrow weighs down my heart

and fills it with bitter grief.

Endless pain and sighs your only gifts

and fear grabs me by the entrails

that I might never again see the glory of sun

forgotten here and as if buried long ago.

Enzio is also credited with the sonnet based on the original lines in Ecclesiastes 3:2, and

translated from the Italian in the mid-19th century by Dante Gabriel Rosetti. However, again,

scholars are in disagreement on whether this could be rightfully attributed to Enzio. In any event,

it is lovely.

Tempo vene che sale e chi discende,

e tempo da parlare e da tacere,

e tempo d’ascoltare a chi imprende,

e tempo da minacce non temere;

e tempo d’ubbidir chi ti riprende,

tempo di molte cose provedere,

tempo di vengïare chi t’offende

tempo d’infignere di non vedere.

Però lo tegno saggio e canoscente

colui che fa sui fatti con ragione

e che col tempo si sa comportare,

e mettesi in piacere de la gente,

che non si trovi nessuna cagione

che lo su’ fatto possa biasimare.

On the Fitness of Seasons

There is a time to mount; to humble thee

A time; a time to talk, and hold thy peace;

A time to labour, and a time to cease;

A time to take thy measures patiently;

A time to watch what Time’s next step may be;

A time to make light count of menaces,

And to think over them a time there is;

There is a time when to seem not to see.

Wherefore I hold him well-advised and sage

Who evermore keeps prudence facing him,

And lets his life slide with occasion;

And so comports himself, through youth to age,

That never any man at any time

Can say, not thus, but thus thou shouldst have done.

I hope Enzio found consolation in these lines from Ecclesiastes when restless pacing in his

barred room at night. Meanwhile, he certainly had not forgotten to dream when he wrote these

lines [translation by Malve von Hassell]:

E vola al regno suo lontano,

al suo castello in mezzo al mare azzurro,

il falconello, e il cielo empie di gioia.

It flies far away to claim its dominion,

sailing to its castle in the middle of the blue sea,

the little falcon, and the sky bursts with joy.

Sources:

Panvini, Bruno. La scuola poetica siciliana: le canzoni dei rimatori nativi di Sicilia

Firenze L.S. Olschki, 1955.

Pascoli, Giovanni. Poemi Italici e Canzoni di Re Enzio. IV Edizione, Nicola Zanichelli editore,

Bologna, 1928.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel and Sally Purcell. The Early Italian Poets (English and Italian Edition).

University of California Press, 1982.

Thornton, Hermann H. The Poems Ascribed to King Enzio, in Speculum, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Oct.,

1926), pp. 398-409, published by: Medieval Academy of America.

Photo attributions:

1. Palazzo Re Enzo, Bologna: By Patrick Clenet – Patrick Clenet, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=285722

2. Enzio of Sardinia, coat of arms, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/20/Enzo_of_Sardinia.jpg

3. Image of imprisonment of Enzio after the battle at Fossalta, by Giovani Villani – http://www.stupormundi.it/images/Enzo_Codice_Chigi.JPG